June 4, 2012

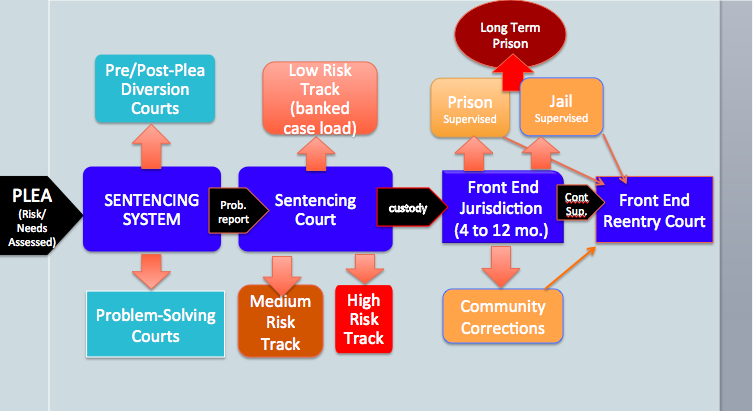

Click on the image below for a copy of the COURT-PRISONER JURISDICTION CHART

Having just led a 3 hour training on the efficacy of Front-End or Early Intervention Reentry at the NADCP Conference in Nashville, I had the opportunity to address a meeting of State Drug Court Coordinators. Even though exhausted from the training, I jumped at the chance to speak to policy makers and representatives of policy makers in their states. I described the potential of the Early Intervention Reentry Courts and the fact that I was happy to share my ongoing research on where court-prisoner jurisdiction existed in states across the nation. [Clicking on the image on the left, will take you to the data on those connections].

Having just led a 3 hour training on the efficacy of Front-End or Early Intervention Reentry at the NADCP Conference in Nashville, I had the opportunity to address a meeting of State Drug Court Coordinators. Even though exhausted from the training, I jumped at the chance to speak to policy makers and representatives of policy makers in their states. I described the potential of the Early Intervention Reentry Courts and the fact that I was happy to share my ongoing research on where court-prisoner jurisdiction existed in states across the nation. [Clicking on the image on the left, will take you to the data on those connections].

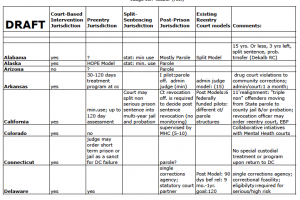

I noted that since January, I’d contacted representatives from over forty-five states (many of them, the state coordinators themselves) to determine where court jurisdiction existed that might impact persons in prison or those leaving prison. After looking at the data, a pattern emerged. There were relatively few states that gave their courts jurisdicition to supervise offenders after a completed prison sentence. But over 90% of states appeared to give their judges authority to recall an offender within a limited statutory period immediately after sentencing. Some individual judges or courts were doing this on a case by case basis, while others were using short term prison sentences systemically, as state policy to reduce prison terms for non-violent offenders (and prison populations). Texas, Ohio, Indiana, and Missouri are just four examples of states that are using their front end jurisdiction to recall offenders from prison (most often, within 3 to 12 months of sentencing) and return them to their communites for continued court supervision, as well as rehabilitation services. (see: Early intervention Reentry Makes its case at Conference)

As I finished my comments, i concluded by saying that It was my hope that policy makers and their representatives will take the opportunity to review the court jurisdiction chart above (though it is a work in progress) to learn what jurisdictional opportunities some state courts have used to reduce prison terms.

What I forgot to ask of the State Court Coordinators, I as of them and all of you now. If you have relevant information on your state’s court-prisoner jurisdiction (whether you are a policy maker or otherwise), please contact me with that information. Review the State/Prisoner Jurisdictional Chart above for errors or omissions, so that we can fill in gaps, and correct mistakes in the data provided. We all need to better understand existing court-prisoner jurisdiction among the states, if we are to reduce prison terms for non-violent offenders’ and reduce prison over-population.